WASHINGTON — Fifty years ago, U.S. Army Captain Steve Yedinak returned home from Vietnam believing that he had led covert operations that contributed significantly to the U.S. efforts to counter communist infiltration from the North into South Vietnam.

FILE – Soldiers of the U.S. 25th Infantry Division dangle their feet over the sides as they are transported by helicopter into an operational area in the Mekong Delta southwest of Saigon, Aug. 9, 1967. The unit was on a search and clear operation. Photo: VOA

Yedinak, now 77, left behind more than 200 local troops who had fought alongside U.S. forces. Ethnic Cambodians living in South Vietnam, the Khmer Krom of Task Force 957, Mobile Guerrilla Force (MGF), were “fun to be with,” he recalls, “and they were vicious.”

They weren’t a well-known force, during or after the war, and for years Yedinak has worked to obtain recognition for the Khmer Krom fighters’ contribution to the U.S. war effort.

To that end, he teamed up with Scott Walker, an advocate for the Hmong and Montagnard fighters who, after the war, settled in Minnesota. Walker succeeded in obtaining recognition for their efforts from the state Legislature in 2012.

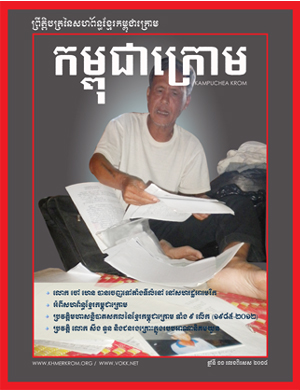

Steve Yedinak is working to obtain recognition for Khmer Krom fighters he led in the Vietnam War. Photo: VOA

Obtaining that same appreciation from Congress has eluded Yedinak and Walker. The latest iteration of a resolution recognizing the Khmer Krom and others was introduced in the House in July.

The problem is that the Vietnam War isn’t something members of Congress and their staffers know or care about, Walker said.

“The Vietnam War is not taught much in our school system and so the people who do know about the war know generally what happened,” said Walker, who with Yedinak, went office to office in Congress, offering specifics about the fighters’ role.

In 2016, Walker and his team learned filmmaker Ken Burns was making a 10-part, 18-hour documentary film series on the Vietnam War. Burns’ previous projectshave generated record-breaking numbers of U.S. viewers, leading the duo to think they would be able to focus on lobbying for the fighters to be recognized, rather than through their education efforts.

Ken Burns participates in the “The Vietnam War” panel during the PBS portion of the 2017 Summer TCA’s at the Beverly Hilton Hotel in Beverly Hills, Calif., July 30, 2017. Photo: VOA

Then they learned that there were no plans to include the Khmer Krom, or even the better-known fighters, in the production.

Upon learning that, “we were absolutely devastated,” Walker said.

The Burns documentary covers the war’s main events, said Brian Moriarty, the publicist for the well-reviewed series that begins on September 17 on PBS stations nationwide.

“No Cambodians or Laotians are interviewed in the film, which focuses on the experiences of Americans and Vietnamese during the war,” Moriarty told VOA Khmer via email. “It does mention Vietnam’s invasion of Cambodia after the war, and other military actions there, but we wouldn’t have any access to Cambodian soldiers who fought alongside U.S. troops.”

FILE – Military traffic is halted as U.S. Army engineers finish repairing a pontoon bridge damaged by a Viet Cong underwater mine, August 1968. Linking Saigon with the Mekong Delta, the bridge over the Oriental River replaced the permanent bridge, blown up by the enemy. Photo: VOA

An extended relationship

The Khmer Krom had a long history of helping the U.S. fight the Vietnamese communist guerillas in the Mekong Delta, where they were recruited into units of the Civilian Irregular Defense Groups (CIDG).

The CIA outlined the importance of using Khmer Krom counterguerrilla forces to fight the Viet Cong in an August 1962 executive memo.

“Efforts to counteract Viet Cong small unit tactics with primary or sole reliance on regular armed forces is to some extent like trying to destroy a hundred thousand flies with artillery,” wrote E.H. Knoche, assistant to then-CIA Director John A. McCone. “In large part, guerrillas must be isolated by counterguerrillas composed of inhabitants in place.”

FILE – In this April 28, 1965 file photo, U.S. Marine infantry stream into a suspected Viet Cong village near Da Nang in Vietnam during the Vietnamese war. Filmmaker Ken Burns said he hopes his 10-part documentary about the War, which begins Sept. 17, 2017. Photo: VOA

Yedinak’s troop usually moved deep into North Vietnamese Army (NVA)-controlled areas for four to six weeks at a time.

They fought without artillery or close air support, and had little hope of a helicopter medevac. On a mission code-named Blackjack 31, the MGF survived 52 engagements, captured prisoners, booby-trapped NVA base camps, and gathered intelligence in an operation that spanned the second half of 1966 and early 1967, according to Yedinak’s self-published book Hard to Forget.

“We could not have done what we did without the support of those people,” Yedinak, now a retired U.S. Army lieutenant colonel, told VOA Khmer recently. He added the recognition he seeks from Congress for the Khmer Krom is nothing more than a plaque or a written commendation “for the sacrifice that they made on behalf of American fighting forces.”

The Khmer Krom also fought with Americans in Cambodia, according to a memorandum signed by President Richard Nixon in April 1970.

FILE – A South Vietnamese soldier holds his personal belongings in a plastic bag between his teeth as his unit crosses a muddy Mekong Delta stream in Vietnam near the Cambodian border, March 11, 1972. His unit was charged with stemming Communist infiltrat. Photo: VOA

Declassified CIA documents posted on the CIA’s Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) site show that four battalions of 2,100 Khmer Krom troops were transferred to Cambodia on May 2, 1970, a little over a month after General Lon Nol staged a coup against Prince Norodom Sihanouk and formed a U.S.-backed government on March 18, 1970, according to a memorandum from Henry Kissinger on April 29, 1970.

At the time, there was growing opposition in the U.S. to the war in Vietnam and the Cambodia incursion surprised the American public.

Many in Congress inquired about the Khmer Krom transfer. In a memo to CIA Director Richard Helms, Legislative Counsel John Mauray highlighted the concerns that the Khmer Krom would be used “strictly in support of the U.S. effort in Vietnam.”

News of the “secret invasion” of Cambodia sparked U.S.-wide protests, which culminated in the National Guard shooting dead four students at Kent State University on May 4, 1970, and police fatally shooting two students at what was then known as Jackson State College on May 15, 1970. Nixon withdrew American troops from Cambodia soon after.

FILE – Ohio National Guard moves in on rioting students at Kent State University in Kent, Ohio, May 4, 1970. Four persons were killed and 11 wounded when National Guardsmen opened fire.

The Khmer Krom “served two ways,” Walker said. “They supported the United States clandestinely” in Vietnam, and officially, in Cambodia.

A complicated history

But recognition continues to elude the Khmer Krom.

Part of this is due to their history, starting in the middle of the 17th century when Vietnam occupied Cambodia’s Mekong Delta area. France occupied the region in the 19th century, and largely kept the antagonistic Khmer Krom and Vietnamese separated until its Cochin-China territory reverted to Vietnam at the end of the First Indochina War in 1954.

By then, the Khmer Krom were an anti-Vietnamese, anti-communist minority in the delta, and many of them were recruited by the French for commando units, said Shawn McHale, an associate professor of history and international affairs at George Washington University who specializes in Southeast Asian and Vietnamese history.

In the 1960s, “when the Americans came in … and realized [the Khmer Krom] were an effective fighting force, they recruited them,” McHale said.

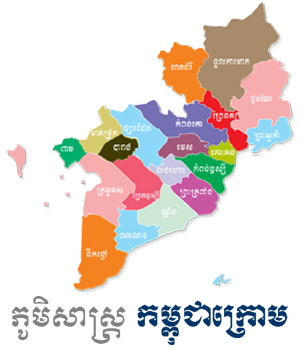

A map showing Cambodia and Vietnam. The Mekong Delta is the tip of land at the southern point of the two countries.

Retired U.S. Army Lieutenant Colonel Yedinak tapped into the Khmer Krom’s yearning for their ancestral land as he molded the MGF.

“They thought they were being recruited and trained to take care of Ho Chi Minh and other local government officials,” he said, adding that the Khmer Krom believed their reward for defeating Ho’s communist forces would be a return of the Mekong Delta to Cambodian rule.

“We did not disabuse them of that notion” because the Americans wanted tough, motivated fighters, Yedinak said.

The tactic worked. Chao Reap, a former Khmer Krom commander who now lives in Seattle, told VOA his comrades fought with the Americans in part because they wanted to regain the Mekong region, where they were treated by Vietnamese authorities like second-class citizens.

After the war, the few Khmer Krom who emigrated to the U.S. “had difficulty in putting forth their position,” McHale said. “They don’t have good PR and that really hurts them.”

Pushing for recognition

In July, Representative Sean Duffy, a Wisconsin Republican, introduced H. Res 491with two co-sponsors — Representatives Ed Perlmutter, a Colorado Democrat, and Glenn Grothman, a Wisconsin Republican.

A map showing Cambodia and Vietnam. The Mekong Delta is the tip of land at the southern point of the two countries.

The resolution “affirming and recognizing the Khmer, Laotian, Hmong, and the other ethnic groups commonly referred to as Montagnards of Cambodia and Laos who supported and defended the United States Armed Forces and freedom in Southeast Asia” is now with the Subcommittee on Asia and the Pacific.

“Congressman Duffy believes that the people supporting our troops deserve recognition,” Mark Bednar, a press officer for Duffy, told VOA this week. Duffy is “very passionate about recognizing the contributions of Hmong, Montagnard and Khmer freedom fighters who helped United States service members.”